Chianina, from rags to riches 15 Novembre 2010 – Posted in: Archivio

Val di Chiana used to be an extensive and unhealthy marsh until the hydraulic engineers working for the Grand Duke Leopoldo di Toscana drained the area. The drainage started by the mid half of the XIV century by the excavation of a complex system of canals and was finally carried out after more than four centuries. In the meantime the typical quadrangular farmhouses, with their peculiar dovecote, were projected and built. The credit of this drainage and regulation, a great achievement for the employed intelligence and resources must be given mostly to the true driving force of the excavation of the canals, the only source of energy pulling the equipment: the autochthonous oxen, the Chianina breed, with their white coat and the slate grey muzzle, reared in this area and used in agriculture for at least 22 centuries. They used to be (and still are) gigantic oxen, with extraordinary strength and resistance, incredible tolerance to high temperatures and sunstroke. No other animal could bear the effort and the hardships of the work of rebirth of Val di Chiana. After many centuries, thousands of years working more than ten hours a day for even two hundred days a year, the importance of the race started to decrease facing the arrival of steam engines and later on of combustion engines. The subject of many rural paintings depicted by the Macchiaioli started to turn into one of the most juicy gastronomic legends.

Its characteristics, the gigantic size (it is considered one of the biggest bovine breed in the world, the height of the withers in adult bulls can be two meters, and they can weight up to 17 tons), the rapid growth and its precocious breeding, are combined with extraordinary resistance to hard environmental conditions and ease in calving. These elements are clearly attractive to farmers, while the exceptional gastronomic qualities are particularly appealing to consumer market. Its lean meat with a wide array of flavours is the key of its international success and it is considered as the best beef in the world. Nowadays it is successfully bred in the USA as well as in Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Mexico, South Africa, Mozambique, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Ireland and Russia.

Its characteristics, the gigantic size (it is considered one of the biggest bovine breed in the world, the height of the withers in adult bulls can be two meters, and they can weight up to 17 tons), the rapid growth and its precocious breeding, are combined with extraordinary resistance to hard environmental conditions and ease in calving. These elements are clearly attractive to farmers, while the exceptional gastronomic qualities are particularly appealing to consumer market. Its lean meat with a wide array of flavours is the key of its international success and it is considered as the best beef in the world. Nowadays it is successfully bred in the USA as well as in Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Mexico, South Africa, Mozambique, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Ireland and Russia.

In a “real” butcher in Florence (or Siena, Arezzo, Massa) and wait to be served in front of an old-fashioned Tuscan butcher, the kind of hale, imposing man, with hands as big as spades. The kind of man who handles knives, carving knives and axes to de bone, take meat off the bones, chop, beat, mince, who solemnly slices ham and bacon. In short, a competent and gifted butcher, who can select the side of the beef, divide the cuts and advise customers about the best cuts for the different cooking. What? You do not know anybody with these characteristics? Of course, such figures are as rare as the albino rhino, yet they still exist in few places (Cortona, Greve in Chianti, Montepulciano or Panzano). Well, the supermarket is certainly faster, everything is visible, clean, pre-weighed, priced, dated and low fat. You do not need to ask, show your poor cooking experience – which allows the butcher to give you whatever he wants – yet you have no chance to control quality other than with your sight. Is it going to be tender? Will it smell good? Is it cut correctly? Did it hang long enough to mature?

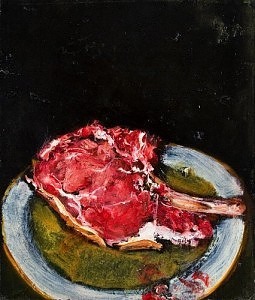

Hanging to mature, the secret of a juicy bistecca alla fiorentina, ‘beefsteak Florentine style’! The meat should be hanging for at least 10/14 days after slaughtering… If this is not well done, the meat will be tough, unable to retain its juice during cooking. Today this delicate phase of biochemical maturing of the meat is made in sterile rooms at steady temperature between 0° and +3° C. Yet some people still remember the times (1050s) when a renowned host in Florence used to improve the process by tying up the entire loin of young beef into a jute bag and let it hanging for some days from the ceiling of the… toilet! Not exactly the most hygienic procedure, however the activity of the bacteria in the room gave extra speed to the maturing of the meat and the steaks were incredibly tender and savoury.

The production and consumption of meat in Italy has changed dramatically over the last decades. The ruling aversion to fat, started in the 70s, widely conditioned eating habits and influenced cattle rearing and slaughtering. In practice beef in Italy is 27% less fat than the beef sold twenty years ago. Anyone who has had the chance to take the great pleasure to taste a thick and juicy Chianina steak, hung long enough to mature and coated with fat, knows well that fat is what gives taste to the meat, it makes it tender and sweet, and makes its flavour intense. The “new” beef is the result of lab researches, comes from intensive breeding and is not suitable to classical maturing so they dry up rapidly during cooking and do not taste good if the flame is too high. If a butcher or a host give you a steak whose size decreases, and that loses a lot of liquids where taste and nutritional values are contained, he is more than incompetent. If you have even been told that loin is Chianina… then he is also a wrongdoer. No other beef is so low in fat and tasty, tender and firm at a time, a kind of meat where nothing is thrown out because fat is only on the surface, and therefore ideal according to the rules of modern dietetics. The classical Chianina steak is so rich in flavour that it has no comparison with extensive livestock farming. It is “modern” meat with old-fashioned taste.

We need to specify the meaning in Italian of the word “beef-steak” (bistecca), which should not be confused with the “minute steak” (fettina, called bistecca as well). In Italian the word “steak” first appeared in the early eighteenth century, when English travellers coming to Florence during the celebrations of San Lorenzo used to see quarters of bullocks of Chianina sliced 5cm thick roasting on the grills under Palazzo della Signoria. The people in Florence and the Italians started to call the T-bone steak Bistecca, the only cut of loin where the T bone separates the fillet from the sirloin. The steak is never less than 5/6cm thick and should weight between 900gr and one kilo.

The thin steaks that butchers (except in Tuscany) attempt to sell you after slicing them from the leg (maybe using the slicing machine), are just as far from T-bone steaks as Saddam Hussein from Mother Theresa of Calcutta.